Motherhood and Dance

Wayward daughters and their loving and concerned mothers are a feature of many ballets including: Giselle, La Fille Mal Gardée and Romeo and Juliet. Typically the mother figure will be paraded on stage only to sit idly in the corner as her daughter confesses her love for a prince who will inevitably break her heart. Seated decoratively on the side of the stage, the mother’s role is significantly diminished. Even in modern ballet’s, such as Mata Hari, the strong female protagonist’s maternal role is short-lived as her remaining living child is kidnapped. Indeed, the traditional narrative of ballets where the main roles are dominated by young girls seems to be suggestive of an overwhelming sentiment: there is no place for a mother on stage. In 2025, this narrative is shifting and PBT is at the heart of this change.

Juggling Motherhood and a Professional Career

A great anxiety for many pregnant dancers, as publicly expressed by Dutch National Ballet Principal Anna Ol, is the fear of not being able to get back in ‘ballet shape’ after they have given birth to their child. Indeed, when a woman is pregnant, her body changes to accommodate the needs of another life. Women will gain weight, they will lose physical strength, their hips will broaden and their breasts will enlarge. These can all be very challenging transformations for a dancer who has been committed to a single aesthetic her entire life.

Ballet mothers may also feel that they are under pressure to sacrifice some of the time they should spend with their child to maintain peak physical condition or alternatively, be forced to decelerate their career to care for their baby. Pregnancy then puts the dancer in a predicament and can trigger the belief that she is no longer fit for either job - as a mother or a dancer.

In addition to their own critical inner monologue, pregnant dancers may fear discrimination from employers and colleagues. There is empirical evidence to justify these concerns with one study published in the American Journal of Sociology finding a 10% decrease in competency ratings for pregnant women. As a result, embracing motherhood can be extremely challenging as dancers battle mental, emotional, physical and even logistical challenges.

Choosing When to be a Mother

It is indisputable that in addition to the soft melodies of Tchaikovsky, dancers must keep their ears open to the sound of their biological clock. A dancer’s career may begin when they are 18 and end when they are 40 depending on multiple factors including injury and employment opportunities. As a woman’s peak reproductive years occur between her late teens and twenties, job promotions and prime fertility tend to intersect. Dancers are then forced to make a difficult decision: stop dancing temporarily/long-term and become a mother or keep dancing and risk the possibility of never having that choice.

Redefining the Role of the Mother

Social Media has played an important role in redefining the role of the mother in the ballet world. Principal dancers like Mathilde Froustey (Paris Opera Ballet), Iana Salenko (Staatsballett Berlin) and Jurgita Dronina (Canada National Ballet) have all taken to their socials to share with their followers the beautiful complexities of being a mother and a dancer. Honest about the mental and physical struggles they have faced, these dancers spread a message of empowerment, perseverance and incredible multi-tasking skills. In an interview with Dance Masterclass, Principal dancer, Polina Semionova even expresses finding a deeper connection with the art form coupled with her eagerness to rush back home to be with her child post-performance.

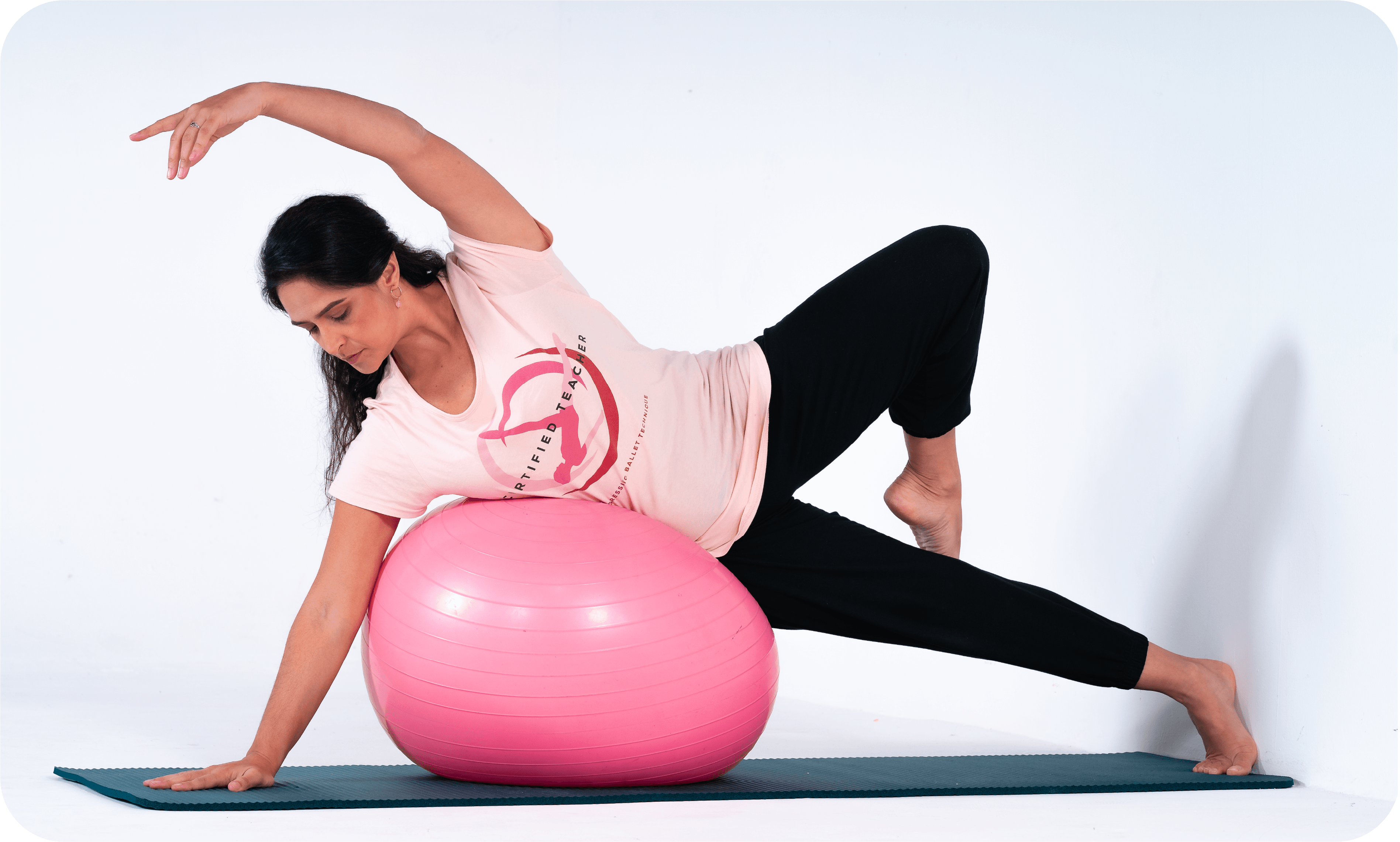

PBT and Postpartum Exercises

Marie Walton-Mahon’s innovative methodology, PBT (Progressing Ballet Technique) can help dancers reconnect with their bodies post pregnancy. The expertly crafted exercises are designed to enhance proprioception, correct alignment and refine muscle activation so that dancers feel empowered in their learning. The emphasis on core stability addresses a common postpartum condition, diastis recti, where the left and right abdominals separate. The method allows mothers to return to ‘ballet fitness’ in a sustainable and healthy manner, ensuring that they have the tools and physical strength needed to juggle a stressful but rewarding life as a mother and a dancer.

The Changing Role of Mothers in Dance

As sustaining a ballet career as a mother becomes more plausible and more accepted thanks to the testimonies of principal dancers and legislative reforms, which ensure paid leave for mothers, the number of pregnant dancers is increasing globally. Choreographers are now under pressure to inform and be informed by this cultural shift, ensuring that their creation meets the needs of an evolving audience and workforce. It’s time to step away from the narratives of young girls falling tragically in love and instead endeavor to explore the complexities of motherhood in all its beauty.

What we see on stage is both affected by and affects the time in which it is written. As a community, we must ensure that we are writing a different story: a story that does more than just include mothers, but puts them front and centre stage.

Sign up to our newsletter

Receive tips, news, and advice.